His soft words and engaging smile were transformed to thunder in an instant, as the sound of a blender suddenly cut in from the kitchen. A single “Oi!!”, along with a throat-slitting gesture, was all it took. No-one moved much after that. Alexandre Mazzia is a renowned chef, runs his ship tight, and wasn’t going to tolerate the recording of his video interview being interrupted. I checked the audio levels and dragged my attention back from the incredible smells wafting to us from the direction of the said blender, as Alexandre picked up where he left off, sweetly explaining that his cuisine must absolutely never be called ‘fusion cuisine‘.

On the up and up

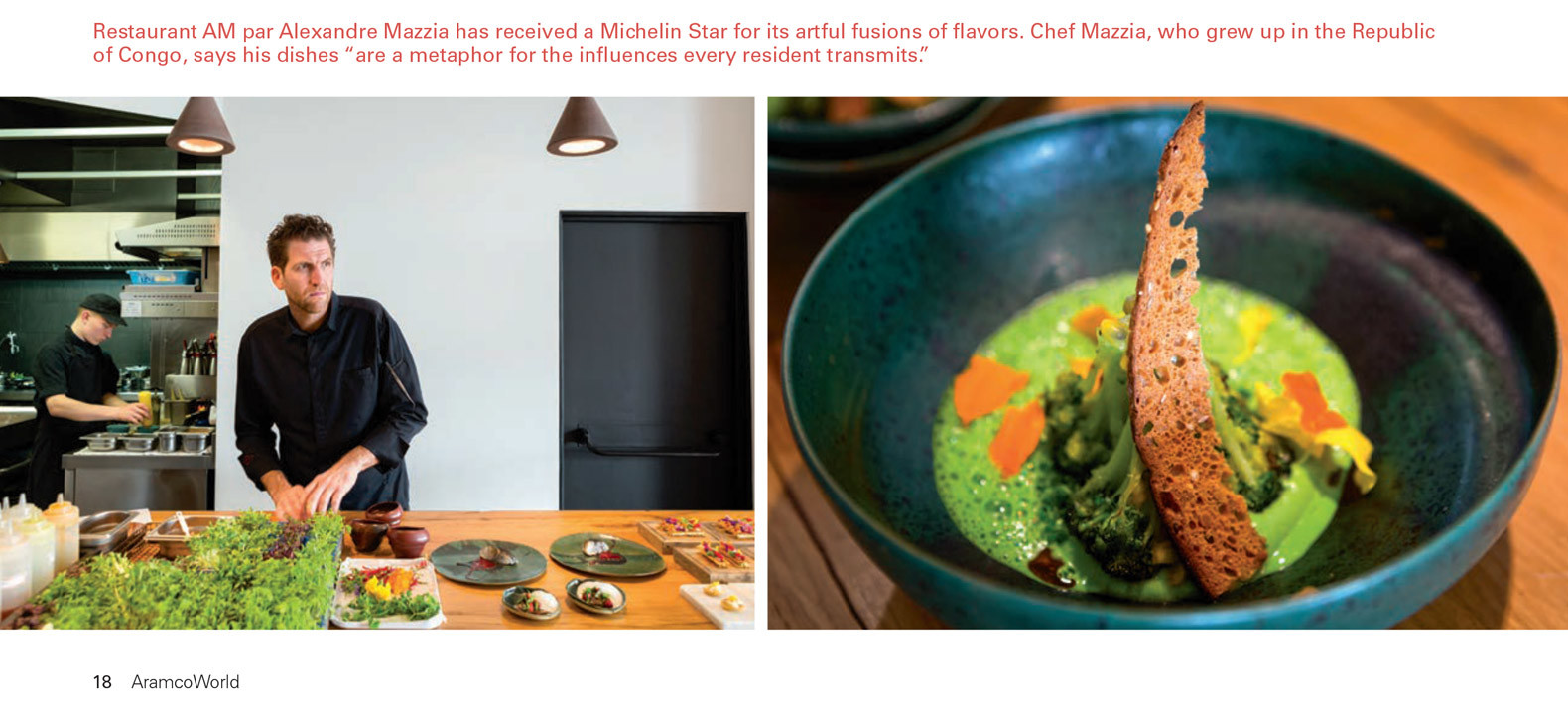

I was in Marseille and this wasn’t the first time I’d met Mazzia, part of a wave of younger chefs who are putting the city firmly on the haute cuisine map of France. A few years before, I’d been sent as photographer by the New York Times to the restaurant where he was then head chef (for a travel feature on Marseille). I’d been struck then by the beauty – as well as the extraordinary taste combinations – of his creations, which marry flavours from the sub-continent with South of France produce (Alexandre is Marseillais but grew up in the Congo). Things have since moved on: he now runs his own restaurant, A.M., which books out 2 months in advance, and has picked up a Michelin star. Today, I was interviewing him and taking his portrait for a prominent 6-page feature and video for Aramco World magazine. For this piece, about Marseille’s cuisine, the global influences that make it unique, and its impact on cooking across France, Alexandre was the perfect interviewee to represent the haute cuisine end of his city’s culinary scene.

Hot-blooded and noisy

On this assignment, writer and photographer were to work together, and I was happy to make the trip with Tristan, travel writer and friend. We’d last collaborated on a reportage about the film industry in Ouarzazate and Marseille is certainly much closer to home than Morocco. But while the city sits firmly in the South of France, Marseille is quite unlike the French Riviera. France’s third-largest city, and by far the largest in the southern part of the country, Marseille has its own unique vibe. A true crossroads of cultures, it has been the landing point for arrivals from across the Mediterranean and beyond, since the ancient Greeks set up a trading post here 2,600 years ago. The city is hot-blooded, noisy, and rumbustious. People here are Marseillais first and foremost, and French second. All this diversity and daring plays out in the city’s cuisine.

It was into Marseille that the Greeks first introduced olive trees to France (now synonymous with Provence) and the influence of migration on food is business as usual here. The Marché Capucins in Noialles is unlike the stereotypical South of France market. Blink and you could be in Morocco, or Tunisia: slide past the teeming shoppers, and you can buy exotic fruit, spices, Halal meat, pastillas at an Egyptian food stall or leblebi at a Tunisian soup stall. Last time I’d been a street photographer here, a young market trader had yelled violently and threatened me when he thought I’d taken a picture of him. I’d been quite shaken by it. This time, however, it was all smiles as I photographed and video-ed the market, and I left with gifts of bananas and sweet grapes stuffed inadvisedly into my photographers bag. Marseille is anything if not unpredictable.

Banished: bare legs and booze

To illustrate the story, I shot a range of portraits, food photography and reportage pictures. Tristan and I met spice seller Jiji, whose wares included dried hibiscus and cactus oils; Joseph, a Lebanese baker who’d installed a 15 metre conveyor belt in his vast bakery to cool flatbread and Bêline, the ballsy daughter of a Vietnamese family who founded a large international food emporium 30 years ago. Now running the place, she managed to spare 2 minutes from leading her team for me to take a portrait of her, with arms full of unrecognisable and unpronounceable fruit. Everyone had something to say, mostly loudly, with big gestures and smiles. And everywhere we went, generous Marseillais plied us with snacks, a drink, or a taste of one of their specialities.

Aramco World is god-fathered by the Saudi Arabian Oil Company (see an explanation of its raison d’être on Aramco World’s website) and, as such, the magazine has a couple of taboos in its editorial guidance for photography. No alcohol, shirtless men or women with bare shoulders or legs visible above the knee are to be shown. The first two weren’t a great problem on this assignment (aside from some beautiful food photographs where a glass of wine might have completed the picture). But Marseille would not be Marseille without bare-legged women, and the weather was South-of-France-hot. I headed to the port at sunset to make some wider, scene-setting pictures and B-roll footage of city life, and all I can say is that I am glad that I ate first (incidentally, a Mechouia salad: something of a Tunisian take on the French Riviera staple, salade niçoise, with its tomatoes, basil, hard-boiled eggs, tuna and olives). It took a very long time, considerable patience and a lot of people passing in front of my lens before I got any usable footage.

I knew the magazine wouldn’t publish this picture, but I couldn’t resist shooting (or eating and drinking) it anyway

Knight without a horse

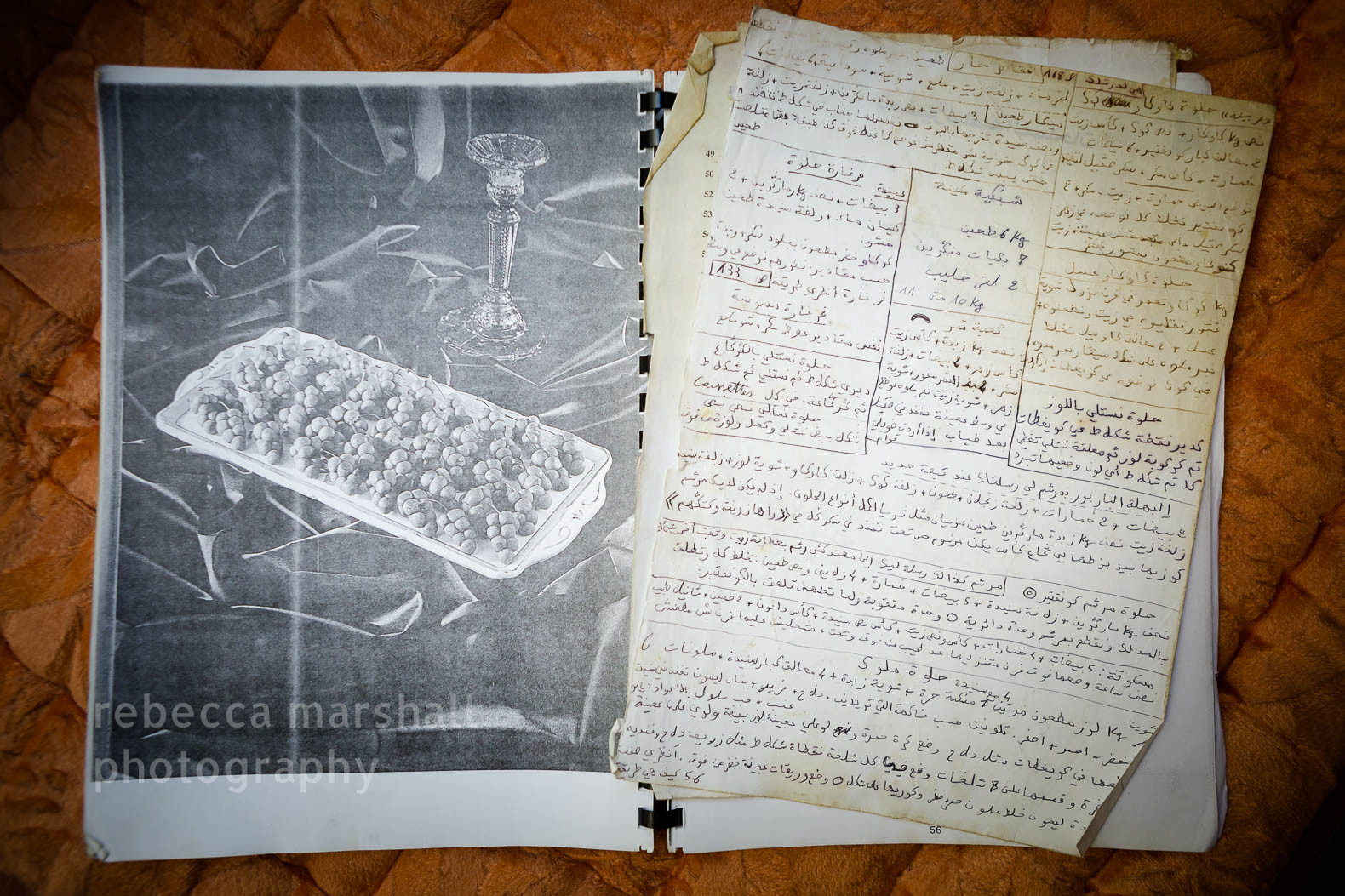

One woman we met has used food as a vehicle to help new immigrants to Marseille. The aim is not simply to feed the hungry though: Fatima Rhazi, through her project Association Femmes Ici et Ailleurs [The Association of Women from Here & Elsewhere], creatively uses cooking and eating, and the social importance of sharing both, to bring immigrants together. In a communal kitchen, she teaches French as well as cookery skills, and so prepares newcomers for life and employment in France. The project is self-funded: using a wealth of shared recipes from Africa, the Middle East and beyond (the association has a large library of recipes, in book and scribbled note form), she and project participants provide catering services to events across Marseille.

After an invitation to lunch on one of the finest home-made tajines Tristan and I had ever tasted, Fatima sat down to tell her story. Moroccan by birth, she was, in her youth, a women’s running champion, competing for Morocco overseas, and later worked as a sports photographer. She maintained that having 6 brothers made her tough – and tough she remains. When Nicolas Sarkozy visited the South of France in 2009, he knighted her chevalier de la légion d‘honneur, the nation’s highest order of merit, for her work. “But I am a knight without a horse!” she jokes. Instead of basking in her own glory, she made the most of this rare opportunity of time with the then-president, asking him to assist 17 migrant families who were struggling to obtain papers to stay in France…which, apparently, he duly did.

Twenty-three delectable courses…

Back at A.M., as Alexandre Mazzia was a key interview subject, it was clearly important that I photograph (and Tristan taste) some of his creations. Alexandre had asked Tristan before our visit if we would like to stay for lunch and so a table had been reserved. I had made a photographer’s request of the exact table that I’d like us to have (with good window light, and reasonable space around it) and the staff understood perfectly. I prepared to work quickly and photograph the key dishes before they got cold, so as not to ruin the food writer’s tasting – and my own lunch. We weren’t shown the menu: instead Alexandre suggested serving a selection of his most representative dishes – which would be perfect for both photographer and writer.

The lunch that followed was truly divine. Matured Simmental beef and Campari, served on the lightest of light miniature flatbreads…. followed by langoustine, carrot, cassava and eggnog…. that led into a red mullet fillet in a duck jus… These were but few in a series of courses than numbered no less than 23 in all. As I munched on a delicately-balanced sculpture of crystallised seaweed with imperial caviar, licorice sweet potato and bottarga, I casually asked Tristan whether, as a prominent travel and food writer, he had ever been invited for lunch (by an establishment presumably delighted to have good, free publicity) – and then presented with a bill. “Oh, only once, many moons ago!” he said, as he took another sip of his current glass of fine wine, that had probably been selected to bring out the flavour of the caviar.

…And one nasty surprise

Now photographers aren’t always so lucky (currying their favour with a free lunch is pointless when a writer has already formed their opinion and filed the piece) and my lingering concern remained. At the end of the marathon meal, which lasted nearly 3 hours, Alexandre came to present us both with a signed, stamped menu as a souvenir of our dégustation. “Nice touch“, I thought, my prior worries now forgotten. However, a waiter still had one last dish to bring to our table. It contained two delectable chocolates and …..the (impressive) bill. BOOM! In a world where magazines are generally restrictive with -or even flatly refuse to reimburse- meal expenses, and journalists and press photographers don’t necessarily have deep pockets, this was a fairly nasty surprise.

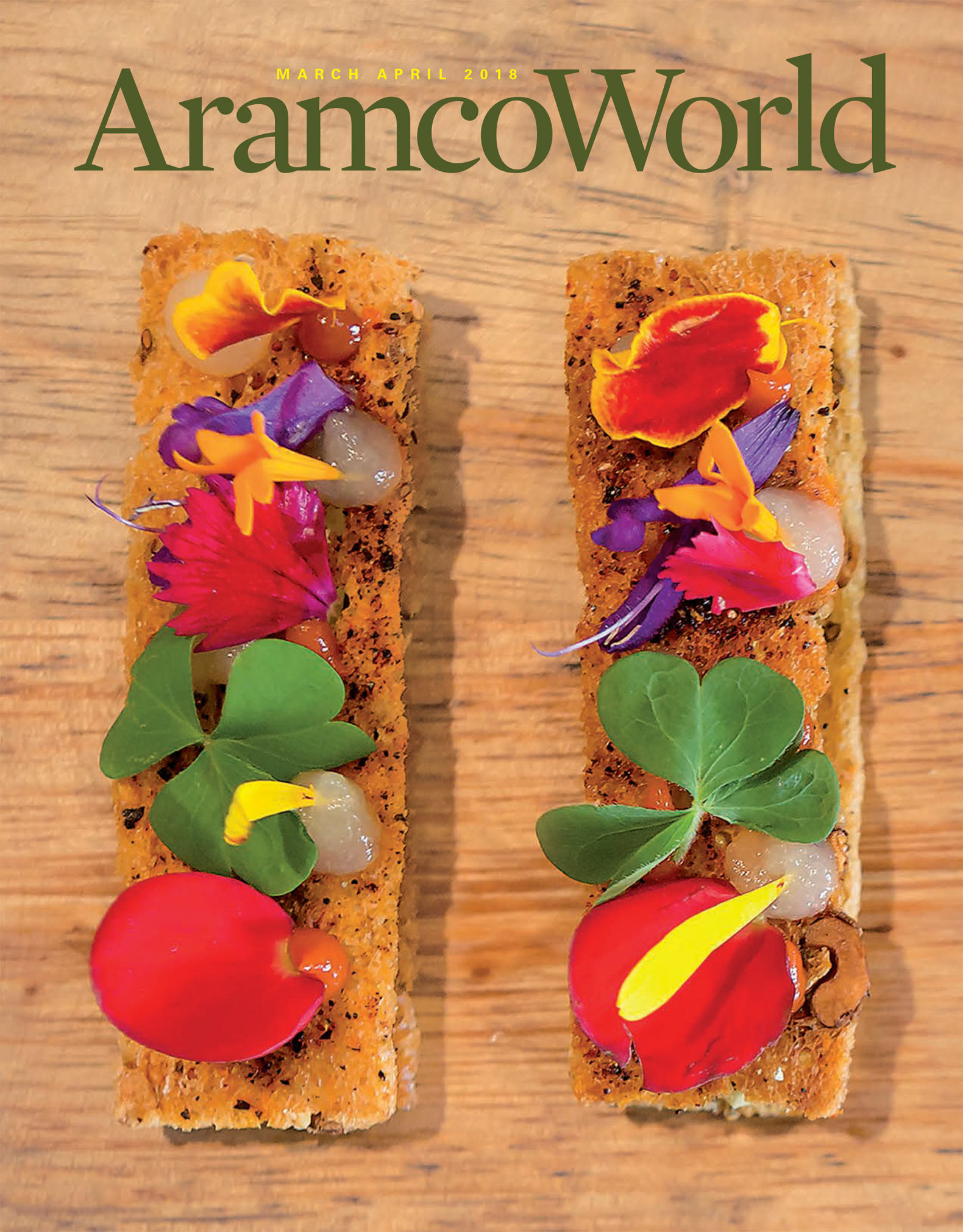

I’m happy to say that the hole in my bank account was temporary. The magazine did, after some discussion, agree to reimburse the expense, and the story has a happy ending. One of the food photographs that I shot during lunch made the cover of the March / April edition of Aramco World. As for Mr Mazzia; a while afterwards, he asked for free copies of the photos I’d taken of his food, to publish on his restaurant’s Facebook page. I coolly explained that as a freelance photographer, I make my living solely from the copyright of my pictures. “No, Alexandre, I don’t give away my images free for commercial publication, and anyway, in this case, Aramco World has bought exclusivity of the whole picture set“. I didn’t feel the slightest twinge of regret.