There were no signs at all to indicate that it was a bar. Only a dull glow of light, oozing out of frosted windows into the humid, autumn dark of this sleeping village, suggested life inside. We’d followed directions carefully, yet, still, opening the door felt daring. The writer, fresh from Germany, pushed me forward – the one apparently best equipped to dare. Inside, a fire in the hearth crackled, loud in the silence. Men, cloaked in black caps and camouflage trousers sat, frozen. A card game was suspended in mid-air. All eyes shifted towards the door. “We’re here at the invitation of Mr Tasso,” I announced, to no-one in particular. The room came back to life. We had arrived in deepest, darkest Corsica to find out about pigs, charcuterie, and how the latter is made there. Mr Tasso, our first pig producer, lived here – in the village of Tasso – and yes, this was his bar.

“Island of Pigs”

Corsica, rising unapologetically out of the Mediterranean 200 km southeast of Nice, has a reputation to live up to. It is part of France, yet its fiery, independent people are known to assert that they have nothing to do with “the continent” – proudly employing their own language to do so. This wild island has unique geology, vegetation cover and even species of flora and fauna that are all its own, and the scent of the ‘maquis‘ (the impenetrable, spikey wilderness that covers much of the island, famous for its capacity to hide outlaws as well as to grow the Corsican herbs that make for both pungent cheeses and heady home-distilled spirits) is, to many Corsicans, the scent of home. Steep, narrow, mountain roads cross the maquis and dense forests to link precarious, isolated villages to each other and the world; and each journey along them becomes a black hole of time, where driving 5 km inexplicably takes 3 hours. A widespread love of hunting and an excess number of firearms has created fertile ground for proud islanders to make their points heard loudly over the years. Yet this unruly and mysterious island is beloved in France and beyond, not least for its gastronomic gifts. On small, family farms, cheeses are made, chestnuts are smoked and clementines ripen… but Corsica’s best known export is probably its charcuterie [dried, cured meat].

German magazine ‘BEEF!‘, a publication entirely devoted to meat, commissioned this assignment – one which would not have suited a vegan photographer. However, my butcher and I are on first name terms; a framed poster of a cut-up cow entitled ‘L’Art de la Viande‘ [The Art of Meat] graces my kitchen wall; and I am really quite happy traipsing around in mud. So when asked “Do you have the time and the lust to make this job for us?“, yes, I did. Yet it turned out that more resistance to hardship was required than expected. The writer had insisted on planning all logistics for the 3 of us (he’d brought an interpreter) himself, yet it wasn’t until after our first 24 hours without food that he boasted that years of war journalism in Iraq meant that he didn’t need to eat, or sleep more than a couple of hours a night. Since he’d booked a one bedroom cottage, and, it later transpired, ignored advice to bring food, the interpreter and I were obliged to join him in his self-imposed deprivation.

Corsica’s best-known charcuterie

Corsican charcuterie is made from the meat of a Corsican breed of pig, ‘Porcu Nustrale‘, which is smaller and generally darker in colour than traditional pigs, and closely related to wild boar. The special, Corsican preparation method was recognised 10 years ago with an AOP badge (a prestigious French food label, guaranteeing origin and production techniques), which stipulates that pigs are raised free-range, eat more than their fair share of wild chestnuts, and that the meat is treated in a certain way, cured for a minimum duration, and is only to be smoked with specific kinds of wood. All the action starts in November: pigs run around everywhere, madly crossing roads in their frenzy for falling chestnuts; farmers drive between abattoirs and small family-run kitchens; cellars are filled with curing meat; orders are placed; and the sweet smell of chestnut smoke creeps out through cracks in smoking houses. Cuts of meat from different parts of the animal are used to make different products, and each one lasts for a different length of time. In pre-fridge Corsica, poor rural families were thus kept in protein throughout the year. Popular items include:

- Figatellu: the pungent liver sausage that is emblematic of Corsica. With a good dose of heart and spleen thrown in, this pungent sausage is to be eaten fresh, within a few weeks, and is ideally grilled, preferably over open flames.

- Coppa: a chunk of neck muscle, marbled with fat, which is salted, smoked using chesnut or beech wood, and matured in the cellar for at least 5 months. 1 pig makes only 2 coppa.

- Lonzu: loin fillet, prepared in more or less the same way as coppa, though it is matured for a minimum of 7 months. It is slightly less fatty, so dries out faster than coppa (and is traditionally eaten first). 1 pig makes 2-4 lonzu, depending on the producer’s perfectionism.

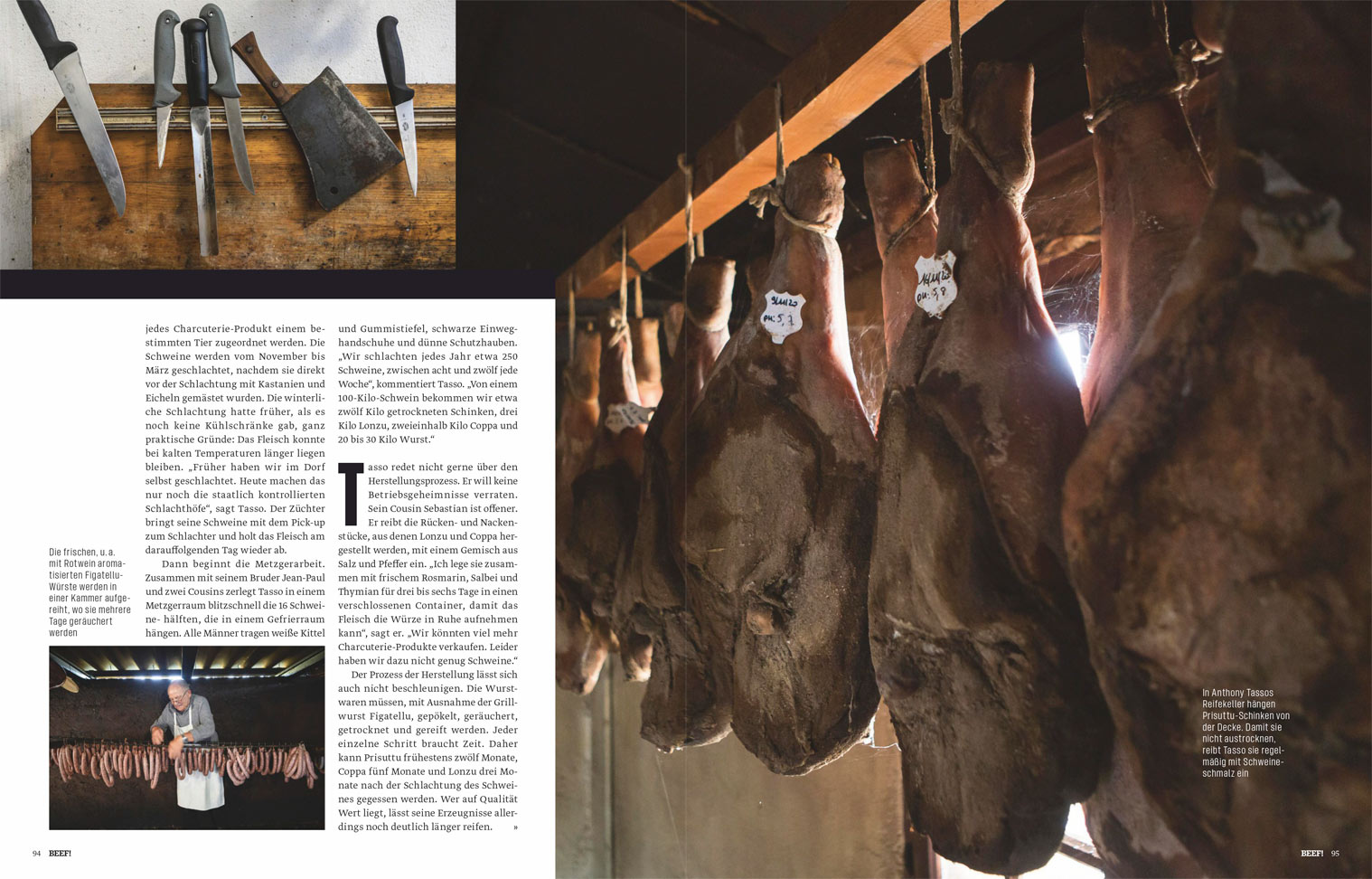

- Prizuttu: the daddy of the island’s pork products – dried, cured Corsican ham. The pig’s back thigh is salted, spiced with pepper and, in some cases, very lightly smoked in chestnut wood, before it matures in the cellar for between 1 and 3 years. Prizuttu sells for up to 150€ a kilo.

Perils of photographing angry pigs

Within hours of landing, I was up to the tops of my boots in mud, protecting my camera from driving rain and trying to keep my balance among the marauding sows who’d rushed to a feeding zone high above the Tasso’s farm. It wasn’t a bad start, yet once back in the dry of Mr Tasso’s 4×4 (where the writer was sheltering), I explained my photographer wish to capture pigs rooting for chestnuts, in the kind of golden, autumn wilderness that characterises the exceptional lifestyle of Corsican Porcu Nustrale. “That won’t be easy,” he muttered. Island pigs, when not being actively fed, want (understandably) as little to do with humans as possible, and they have an endless expanse of dense woodland and maquis in which to escape them. Yet, he said, he would help.

After lurching along many kilometres of muddy track (Mr Tasso professed not to know how many hectares of land he actually has), he spotted a gang of pigs among nearby chestnut trees. One sure-fire way to stop them running away, he told me, was to send his young collie dog to lure the pigs over. It seems that the excitable yaps of a dog inspire instant rage in a pig – one that it cannot resist acting upon. It was a risky enterprise for a photographer, though, crouching on the ground behind the dog. I was about 20 metres away from a giant, livid sow, who was slowly advancing, and so caught up in picture-taking that I was unaware of how close the dog was getting to me. Suddenly everything happened very fast. The pig (not the dog) barked, put its head down and charged; Mr Tasso yelled “Retreat!”; we hurtled down the hill and propelled ourselves gracelessly over a barbed wire fence, on which I ripped my jeans. I reflected later that it was the second time I’d been charged by a dangerous animal recently. Editorial photographers should get paid danger money.

An unwelcome scent of pig offal

As for the next stage of the charcuterie production process, there had been some confusion about our schedule. The writer had thought that a pig was to be butchered by the Tasso family the very next morning, but he was a day ahead of time. So, despite the photographer’s, interpreter’s and even Mr Tasso’s reservations, this intrepid journalist wasn’t to be phased by his lack of local experience, and insisted we travel to another small charcuterie production in the north of the island instead. Owing to the particularities of Corsican roads, over 10 hours of that day were, as a result, spent in the car. The interpreter and I were as green as the forest lining innumerable hairpin bends, and that morning’s absence of food did not assuage our motion sickness. The ex-war journalist at the wheel erratically dodged wild pigs and the occasional oncoming car we met, and we traced and re-traced sections of road as the predictable failure of the GPS connection threw him off route.

Up close to the stuffing of raw liver and other offal into pig guts: a perfect cure for travel sickness

To say we had all had enough by the time we rolled out of the car, at Charcuterie Domestici in the pretty village of Piano, would be an understatement. The interpreter instantly rushed to the bathroom, where she remained for some time, and then, together with the writer, staggered to the bemused charcuterie producer’s lounge, where cuts of pig were discussed from a safe, scent-free distance. I, however, as photographer, was led into a shed, where two kindly gentlemen were stuffing fistfuls of raw liver and other bits of offal and fat into sheaths made from pig guts – the first stage of making figatellu. A short while later, we had to get back into the car to return to Tasso.

Raw pig’s liver, anyone?

That evening, I mutinied. Mrs Tasso took one look at me, and promptly offered me a square meal and a bedroom at her home. My full stomach and sound night’s sleep gave me the energy to photograph further pig butchery action the next day – energy that I fear I would not have mustered otherwise. We had a rendez-vous inside Charcuterie Tassinca, the Tasso’s kitchen-workshop, where the carcass of the first unlucky pig of the season had been driven back from the abattoir.

The Tasso family owns 600 pigs – large scale production by Corsican, non-industrial standards. Mr Tasso, his brothers and cousins, were a formidable team, in their white-soon-to-be-red overalls, hairnets and boots, weaving their butchery magic before my camera. From wielding power tools to deal with the biggest bones, to delicately scattering fresh herbs picked from the garden to lay with salt over pieces of lonzu for seasoning, the Tasso men made short work of the pig. They only paused once, when the BEEF! writer leaned in over the table, cut off a piece of the fresh liver and unexpectedly popped it straight into his mouth. Everybody there, myself included, was surprised. “A cow’s liver, OK, but a pig’s?! I wouldn’t ever risk eating that raw“, muttered one of the Tassos. Perhaps the journalist’s hunger, up until then denied, was at last making a perverse appearance.

The last supper

We had one last charcuterie to visit, in the island’s northwest: that of the Pistorozzi brothers, whose surname alone would be a worthy title for a cut of Corsican cured meat. Pierre-Louis and Thomas genially took us to see their 200 pigs, who frolicked under olive trees beside the sparkling blue Mediterranean; they demonstrated their butchery, salting and meat smoking processes… and then they invited us to join them for a splendid, full meal, made up of their charcuterie products.

After the day’s work was done, a barbeque on the patio was lit, and fresh figatellu, seasoned to a secret family recipe and smoked over chestnut wood, were laid out and thoroughly grilled (a mistrust of eating uncooked pig’s liver not being limited to the Tassos). Meanwhile, a Porcu Nustrale saucisson starter was passed around, and a bottle of good local red wine opened. We worked our way attentively through several delicious cured meats, accompanied by fresh, crusty baguettes, before the main course arrived: filet mignon. Under the watchful gaze of a pair of antlers and 3 rifles on the wall, satisfied smiles spread across our definitively non-vegan gathering, at last.

> See Reportage portfolio